Green energy, grey areas?

Britain’s natural landscapes are rightly treasured, yet the climate crisis demands renewable infrastructure. As turbines appear on hilltops and solar panels proliferate across farmland, we’re left to ask: how do we preserve both countryside and climate?

Words: Matthew Jones | Illustrations: Brett Ryder

I knew they were coming – I’d spotted the telltale symbols on my OS map when planning my route. But as I climbed the hillside, they were hidden from view by a blanket of grey. Unusually, this meant I heard them before I saw them: a ‘whump, whump’ of spinning blades, before a tall, tapering pillar loomed out of the fog.

This was stage 12 of the Cambrian Way, Wales’s finest long-distance trail. I’d spent the past 11 days backpacking through landscapes that had gradually seemed to get lonelier, emptier and wilder – until now. Suddenly, I found myself walking through the Cemmaes Wind Farm, an 18-turbine installation in the heart of Powys. Commissioned in 2002, the site lies directly on the route, which threads its way past a network of access tracks that link a series of 66m/216ft-high turbines.

My reaction was immediate and complicated. In this quiet landscape, the turbines felt intrusive, industrial, wrong. Yet I’d benefit from the electricity these structures would generate. After a couple of days hiking off-grid, I was keen to reach a campsite so I could plug in my phone and recharge my portable power bank. And as someone who loves the great outdoors, I’m acutely aware that climate change poses a grave threat to the countryside.

I know I’m not alone in this cognitive conflict. We increasingly find ourselves caught between two fundamental values: preserving the countryside we love, while protecting it from climate breakdown.

Low emissions, high stakes

The UK Government is committed to reaching net zero carbon emissions by 2050, with an interim target to deliver 100% clean power by 2030. [1] Meeting these targets without renewable energy is, according to the Climate Change Committee, essentially impossible. [2]

Progress has been made. Renewables generated more than half of the UK’s electricity for the first time in 2024, with wind providing the lion’s share. [3] But to hit the net zero target, our low-carbon electricity generation needs to nearly quadruple. That means significantly more wind farms, both onshore and offshore, and a dramatic expansion of solar capacity. The previous Conservative government’s British Energy Security Strategy aimed for up to 50GW of offshore wind by 2030 (the current capacity is about 16GW), while the current Labour government has lifted the de facto ban on new onshore wind farms in England that had been in place since 2015. [4]

The arguments extend beyond climate, too. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine demonstrated the vulnerability of dependence on fossil fuels, particularly gas. In contrast, renewable energy offers energy security – after all, the wind blows and the sun shines, regardless of international tensions or global supply chains. There’s also an economic dimension: the wind industry already supports more than 55,000 UK jobs, with potential for significant growth. [5]

Then there’s the fact that, for many walkers, climate action feels deeply personal. We’re already witnessing changes in our national parks and elsewhere – from increased regularity of flooding in the Lake District, to damaged peat bog in the Peak District. In the Cairngorms, Scottish mountain plateaus, shaped by millennia of freeze-thaw cycles, now see fewer freezing days [6] and less snow cover. We walk to engage with nature, but it’s becoming hard to ignore the evidence that we’re increasingly walking through nature in decline.

Impact on lives and landscapes

Yet acknowledging climate urgency doesn’t change the instinctive reaction many of us have when encountering industrial infrastructure in much-loved landscapes. In Ayrshire, Scotland, turbines up to 251m/823ft tall have received consent, making them the biggest onshore turbines planned for the UK. [7] Solar farms, meanwhile, can occupy huge areas: Cleve Hill Solar Park on Kent’s Graveney Marshes, which started operations in July 2025, is the largest solar farm in the UK, covering some 360 hectares/890 acres. Because of its size, it’s a Nationally Significant Infrastructure Project (NSIP), and so falls outside the standard local planning procedure. [8] For those who seek out the countryside for its sense of untouched tranquillity, the impact of such large-scale development can feel devastating.

Countryside charity CPRE says ‘visual impact’ constitutes the major objection to many renewable-energy planning applications. Critics argue that certain landscapes – particularly upland areas, where wind resources are strongest – possess valuable qualities that industrialisation irreversibly damages. Wind farms are often considered to be temporary installations, because turbines have a finite lifespan (20-30 years) and planning permissions are frequently granted for limited periods (often 25 years). But in that time, the character of a landscape can be fundamentally altered.

Of course, much of our countryside is a living, working landscape, including our national parks. The fells of the Lake District, the slate-strewn mountains of Eryri, the emptiness of the Scottish Highlands – none of these are pristine wilderness, but the product of centuries of farming, mining and settlement (or, in the case of the Highland Clearances, forced eviction). All the same, they’re cultural artefacts. They tell stories about who we are. So, introducing modern industrial structures can feel like bulldozing history.

Admittedly, different landscapes provoke different responses. A turbine on the horizon of intensive agricultural flatland generates less controversy than one crowning a wild hilltop. Solar panels beside motorways draw fewer objections than those covering South Downs chalkland. Context matters, yet renewable potential doesn’t always align with landscape sensitivity.

When it comes to wind, the onshore versus offshore debate encapsulates these tensions. Common sense might dictate that if we need turbines, why not stick them in the sea rather than in the middle of our countryside? Offshore wind has some compelling advantages: stronger, more consistent marine winds generate more electricity; visual impact is reduced; and there’s no competition for land use. [9] The UK’s offshore capacity already leads Europe, and the seas around our coastline hold enormous potential. [10]

However, offshore farms cost significantly more to build and maintain, require extensive undersea cabling and aren’t without environmental concerns. Impacts on marine ecosystems, the seabed and seabirds remain poorly understood. [11] Onshore turbines, conversely, are cheaper and faster to construct, can be more easily community-owned and offer direct economic benefits to rural areas. [12] But they often occupy the landscapes that outdoor-users love, their presence inescapable on many hilltops. For coastal walkers, the calculation shifts again – turbines visible offshore can seem either a reasonable compromise or a blight on an unbroken ocean horizon. There’s no perfect solution, only trade-offs that different people weigh differently.

The ecological equation

Solar and wind farms also raise questions about land use and biodiversity. The UK relies on imports for about 40% of its food; covering productive farmland with solar panels will intensify this dependence. [13] With 69% of UK land devoted to agriculture, even small percentages translate to thousands of hectares. [14] However, the calculation isn’t straightforward. The industry benchmark for solar panel life is 25-30 years, after which the land could feasibly return to agriculture (if the solar farm is no longer deemed necessary for energy output). Similarly, wind turbines require relatively small physical footprints beyond the base and access tracks, with grazing able to continue around them. Compare this with fossil fuel extraction, which can leave land contaminated for decades, or to climate change itself, which threatens to render significant tracts of agricultural land unproductive through flooding, drought or soil degradation.

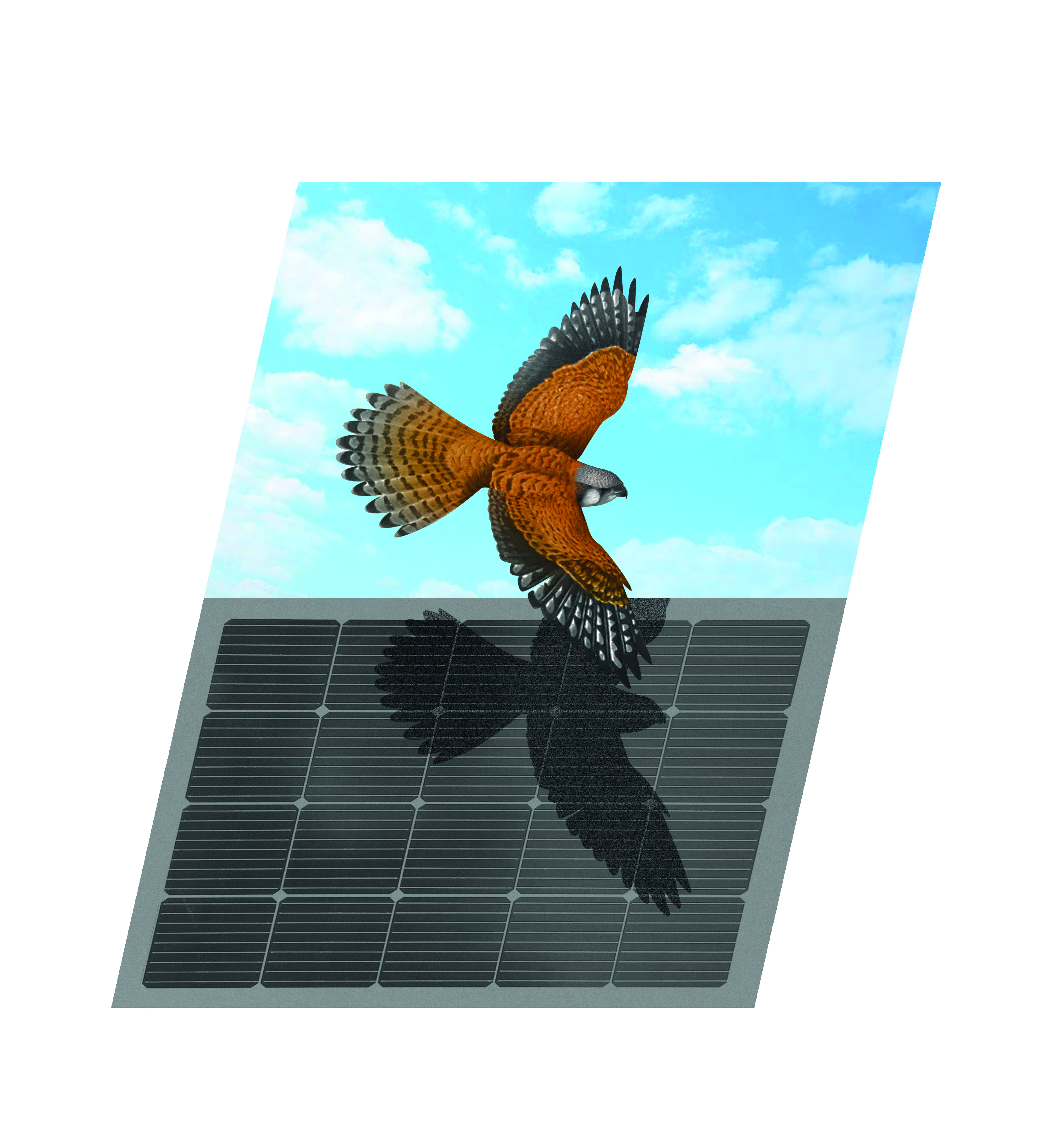

The impact of renewables on wildlife can be significant, though this is notoriously hard to quantify. Wind turbines undoubtedly kill birds and bats, though estimates vary widely as to how many – and it’s a fraction of those killed by domestic cats or collisions with cars, buildings and power lines. However, birds of prey can be particularly vulnerable, as they may collide with blades while hunting. [15] A 2024 Freedom of Information request to NatureScot revealed a total of 71 raptor deaths over the previous ten years as a result of collisions with onshore turbines – though the data relied on voluntary submission of reports. [16] Species killed included golden and white-tailed eagles, ospreys and hen harriers. This means turbines aren’t just visual intrusions, but also active threats to UK wildlife.

On the flipside, solar farms, if managed sensitively, can provide biodiversity benefits. Grassland beneath panels, left unmown and unsprayed, can offer a habitat for wildflowers, insects and ground-nesting birds that have declined drastically in intensively farmed land. Some operators actively manage sites for nature, creating moist scrapes for wading birds or planting hedgerows. One 2016 study based on surveys of several solar farms in the South of England concluded that they supported higher biodiversity than equivalent agricultural land. [17]

Wind farms are more complex. While operational turbines pose collision risks, habitat around them – if managed well – can benefit wildlife. NatureScot’s guidance is that well-sited wind farms have limited effects on birds, but concedes that how birds behave close to wind turbines still isn’t well understood. [18]

Profits, partnerships and pioneering projects

As ever, politics adds another layer. Renewable developments, particularly wind farms, often arrive from outside – developers from elsewhere, with profits flowing to distant shareholders of privatised energy companies. Communities see landscapes transformed, but feel little direct benefit.

This inevitably breeds resentment. When walking the Cambrian Way, I encountered villages visibly divided over nearby wind farm proposals. Some residents seemed to support them – pointing to climate action, job creation, a boost for local businesses – while others felt their landscape was being industrialised without adequate consultation. For outsiders like me, walking through for a weekend, it’s easy to have opinions, but these communities have to live with the consequences.

Some projects have pioneered better approaches. Community-owned renewable schemes, where local residents invest and receive returns, tend to generate far less resentment. When Fintry in Stirlingshire secured a partnership deal with a wind farm developer, it enabled the village to fund its own energy reduction and sustainability measures. [19] If communities have agency and a financial stake, opposition often gives way to support.

What can ramblers do?

For local Ramblers groups learning of renewable proposals near popular paths, the temptation toward kneejerk opposition is understandable. But ‘not in my backyard’-style reactions generally serve neither landscape nor climate. Instead, try to:

• Engage substantively with consultations. Planning processes provide opportunities to influence location, scale and mitigation. Reasoned objections carry weight; blanket opposition less so. Suggest alternative sites, request habitat enhancement and demand improved path access

• Distinguish between types and locations. A wind farm in the Cairngorms deserves different consideration from one in Lincolnshire flatland. Solar panels on warehouse roofs differ from those covering wildflower meadows. Nuance matters.

• Examine alternatives honestly. If not renewables, then what? More gas-fired power stations? Nuclear? Going back to coal? Every energy source impacts our landscape – often invisibly, through factors like climate change, air pollution or damage from activities such as mining and fracking.

• Consider scale. Individual developments may feel significant locally, but must be weighed against national need. We require hundreds of additional turbines and thousands of hectares of solar to meet climate targets. They have to go somewhere. It’s our role to argue where is best.

• Look for compromise. Can developers enhance habitat elsewhere? Fund path improvements? Provide community benefits? Perfect outcomes rarely exist, but negotiations can improve projects.

Greener horizons?

The uncomfortable truth is that loving our countryside means accepting that it will change – either through climate action or climate breakdown. At least solar farms and wind turbines have their upsides. Habitat lost to climate change disappears forever, with no benefit to anyone.

As walkers, our responsibility extends beyond preserving views we personally cherish (though that remains vital). It’s also our duty to ensure future generations inherit landscapes where golden plovers still nest, ancient oakwoods still flourish and footpaths still connect people to functioning ecosystems. If that requires turbines on some horizons and glinting panels on some hillsides, it’s a trade-off we may have to accept.

Matthew Jones is a writer and editor specialising in Britain’s outdoors. A former editor of walk, as well as Scouting magazine, he writes features and gear reviews for outdoor publications and websites. He lives and works in Eryri (Snowdonia). Follow @mattymountains

References

[1] Policy paper, Clean Power 2030 Action Plan. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9888/

[2] Climate Change Committee. (2020). “The Sixth Carbon Budget: The UK’s path to Net Zero.” Available at: https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/sixth-carbon-budget/

[3] National Grid, “How much of the UK’s energy is renewable?” https://www.nationalgrid.com/stories/energy-explained/how-much-uks-energy-renewable SUB’S NOTE: Couldn’t see 2024 stats in this source – but found this one: https://www.renewableuk.com/news-and-resources/press-releases/official-stats-show-renewables-generated-over-half-uk-s-electricity-for-the-first-time-in-2024/

[3a] https://www.greenmatch.co.uk/blog/2021/02/renewable-path-to-net-zero-emissions (SUB’S NOTE: added this source for quadruple quote)

[4] UK Government. (2022). “British Energy Security Strategy.” Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/british-energy-security-strategy

[5] RenewableUK. (2025). https://www.renewableuk.com/news-and-resources/press-releases/55-000-people-now-work-in-the-uk-wind-industry-including-40-000-in-offshore-wind/

[6] Snow Cover and Climate Change on Cairngorm Mountain: A report for the Cairngorms National Park Authority, Mike Rivington (The James Hutton Institute) & Mike Spencer (SRUC), 2020, https://cairngorms.co.uk/documents/snow-cover-and-climate-change-on-cairngorm-mountain-a-report-for-the-cairngorms-national-park-authority/html

[7] Tallest Consented (Onshore): Lethans Wind Farm (Scotland), Daily Record: https://www.dailyrecord.co.uk/ayrshire/uks-tallest-onshore-wind-turbines-33468620

[8] BBC News, “Is UK’s biggest solar farm a blueprint for future?”, Nov 2025, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/ckg4p55725eo

[9] The Crown Estate. (2024). “Offshore Wind Report 2024.” Available at: https://www.thecrownestate.co.uk/our-business/marine/offshore-wind

[10] UTM Consultants, https://www.utmconsultants.com/7-nations-that-are-leading-the-offshore-wind-race/

[11] Furness, R.W. et al. (2013). “Assessing vulnerability of marine bird populations to offshore wind farms.” Journal of Environmental Management, 119, 56-66. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301479713000637

[12] RenewableUK. (2025). “Assessing the Outlook for Onshore Wind” https://www.renewableuk.com/news-and-resources/blog/assessing-the-outlook-for-onshore-wind/ SUB’S NOTE: Couldn’t see how this contained points covered in sentence. See https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/65c4ee44cc433b0011a90aa1/developing-local-partnerships-for-onshore-wind-in-england-government-response.pdf instead (‘it is one of the cheapest generating technologies, can be constructed quickly and can provide tangible benefits for local communities.’)

[13] Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. (updated 2024). “United Kingdom Food Security Report 2021.” Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/united-kingdom-food-security-report-2021 SUB’S NOTE: updated to most recent report: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/united-kingdom-food-security-report-2024/united-kingdom-food-security-report-2024-theme-2-uk-food-supply-sources

[14] Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. (2025). “Farming Evidence: Key Statistics”: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/farming-evidence-pack-a-high-level-overview-of-the-uk-agricultural-industry/farming-evidence-key-statistics-accessible-version

[15] Bright, J. et al. (2008). “Map of bird sensitivities to wind farms in Scotland: A tool to aid planning and conservation.” Biological Conservation, 141(9), 2342-2356.

[16] NatureScot, “Freedom of Information Request - Deaths of Birds of Prey in Scotland from windfarms”, 2024: https://www.nature.scot/doc/freedom-information-request-deaths-birds-prey-scotland-windfarms

[17] Montag, H. et al. (2016). “Biodiversity in solar parks: A case study on the influence of solar parks on plant diversity and grassland vegetation.” Renewable Energy and Sustainable Development, 2(1), 1-11. SUB’S NOTE – see https://wychwoodbiodiversity.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Montag-Parker-Clarkson-2016-Solar_Farms_Biodiversity_Study.pdf

[18] NatureScot, “Wind farm impacts on birds”: https://www.nature.scot/professional-advice/planning-and-development/planning-and-development-advice/renewable-energy/onshore-wind-energy/wind-farm-impacts-birds

[19] Fintry Development Trust: https://fintrydt.org.uk/

Discover more

Walk Magazine

Walk magazine is the the UK’s most widely-read walking magazine

.png?itok=D6Bu-GkL)

News & features

Our latest news, stories, views and opinions on a whole variety of topics related to the world of walking.

Navigating the climate crisis

The evidence is indisputable: our weather is becoming milder, our winters wetter and our sea levels higher. But what does climate change mean for people who work to maintain paths – and for the walkers who use them?