In the footsteps of Jane Austen

Explore new Jane Austen trails, devised to mark the novelist’s 250th anniversary

Words: Phoebe Taplin

One of England’s best-loved novelists, Jane Austen, was born 250 years ago this December. New commemorative trails are helping ramblers follow in her footsteps through the Hampshire countryside where she grew up, and expand the area’s Austen-related walking network

The church bells are ringing as I arrive in Overton. A watchful red kite floats low over the rooftops and soft, burnished fields of barley are peppered with poppies. In the River Test, moorhens step through green mats of watercress under fringes of marzipan-scented meadowsweet.

I’m in this picture-postcard-pretty Hampshire village to try out some new walking routes that trace local links with the novelist Jane Austen. The trails have been created to celebrate the 250th anniversary of her birth by Overton Parish Council and a team of volunteers, backed by local businesses and community groups.

Austen spent her first 25 years in the little village of Steventon. My first trail leads there and back along a waymarked 14km/9-mile route from Overton, exploring connections to the novelist’s life.

Elizabeth Bennet: ‘an excellent walker’

Austen’s characters often walk cross-country, as she did herself. Elizabeth Bennet, the spirited heroine of Pride and Prejudice, is a great lover of the outdoors, ‘crossing field after field at a quick pace, jumping over stiles and springing over puddles’. Mr Bingley’s snobbish sisters criticise the ‘conceited independence’ of going so many miles alone, comment on Elizabeth’s muddy petticoat and wind-blown hair, and conclude she has ‘nothing… to recommend her, but being an excellent walker’. They are put out when Mr Darcy observes that her eyes ‘were brightened by the exercise’. It’s a deliciously Austenian exchange.

The first black-and-white waymark, with its quill logo, points towards the river. Soon after, flint-walled St Mary’s Church stands above the road, its heavy oak door studded with rusted nails. Austen’s brother James was curate here from 1790; it’s the first of several local churches with family connections.

The walk soon leaves the road and follows an idyllic, tree-roofed, riverside path, where birdsong pours out of a tangle of mossy branches, reeds and yellow irises. Through water meadows, I reach the little church in Ashe and spot another rambler holding the same walk leaflet as me. Monika from Sweden is a lifelong Austen fan since finding a copy of Pride and Prejudice in a sale as a teenager. ‘I thought it was very funny,’ she tells me. ‘I laughed so much I actually fell off the couch.’

Austen danced and dined in picturesque Deane House, a mile further on. The sprawling brick mansion and surrounding parkland are exceptionally lovely and you can easily imagine the young writer walking among the sheep and stately beeches. Along the lane, there are hazelnuts ripening and berries turning red in neatly clipped hedges.

The Deane Gate Inn at the junction was once a coaching inn on the road to Exeter. It’s now the smart Palm Brasserie and the walls are covered with Austenalia. I stop for coffee and look at the poster-sized book covers, horse brasses and collages involving quills and little inkpots. ‘They say Jane Austen wrote Pride and Prejudice sitting just over there in the corner,’ says general manager Shinto Mathew, laughing and pointing to a table in the modern annexe.

A Jane Austen trail through the Hampshire of her youth

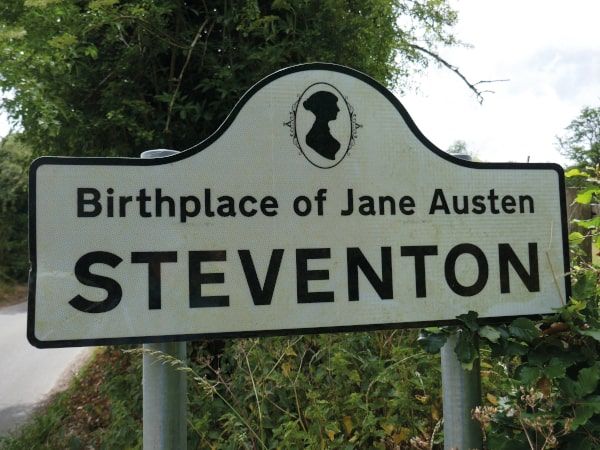

‘Birthplace of Jane Austen’ announces Steventon’s village road sign. The cart track was rough and muddy when her parents moved here in 1771, four years before she was born, her mother ill and travelling in a feather bed on top of the laden waggon.

Today it’s a quiet country lane, lined with tall poplars. Butterflies dance through flowering hedges and the first blackberries are sweetening in the sun. Branches lean over the road from a neighbouring wood, mentioned in one of Austen’s witty letters to her sister: ‘You express so little anxiety about my being murdered under Ash Park Copse… that I have a great mind not to tell you whether I was or not…’

Steventon’s red phone box, decked with celebratory bunting, has become an information point and book exchange. The original rectory, where Austen spent the first 25 years of her life and wrote her first three novels, was knocked down when her brother, Edward, replaced it with a grand new house on the hill above. A flourishing lime tree, on the corner of the lane that leads up to the church, was planted by another brother, James, in 1813. The peaceful church of St Nicholas has sprouted Victorian decorations and a spire, but you can still see an earlier ornate box pew and monuments to the Austen family. A 900-year-old yew tree stands in the churchyard, where James is buried.

Nearby, moths and marbled whites flicker through a small meadow of vetch, mullein, knapweed and lady’s bedstraw. Church warden Marilyn Wright shows me how the young novelist invented fictional marriages on the opening pages of the church register. She points out the scratch dials (showing the times of mass) by the church door and pieces of the pump from the Austen family well. Coachloads of Janeites from around the world will descend on this tiny village in the next few months, including a group from the recently formed Jane Austen Society of Mexico. Marilyn admits to ‘trepidation’, but visitors’ contributions help with the costs of looking after a damp and ancient church.

Exploring Austen’s Steventon, Overton and Alton

Walking downhill from Steventon, a yellowhammer sings staccato notes from the top of an oak and linnets twitter on the telephone wires. There’s a smell of late elderflowers and pineapple mayweed.

The path runs below the railway, past banks of purpling sloes and curtains of bryony, then swings north through parkland to reach Ashe House, once a parsonage and home to Austen’s close friend Anne Lefroy. The handsome brick mansion is a model of Georgian elegance with its wide, arched doorway and peacock fanlight. It’s easy to imagine the late-18th-century occupants holding dances as they did in January 1796, when Austen wrote: ‘At length the Day is come when I am to flirt my last with Tom Lefroy.’

The Overton walking route also passes sites linked to darker moments in the author’s life, such as Anne’s fatal horse-riding accident and another friend’s highway robbery. The circuit starts and ends near The White Hart pub, where I’m staying, a maze of low-ceilinged bars and an outdoor terrace offering hearty pub food. ‘Sixteenth Post Horse Change Daily’ is painted on the outside and there’s still something of the stagecoach-era about it, with buses to Basingstoke and Winchester stopping regularly nearby.

Four shorter Jane Austen walks

Next morning, I travel 27km/17 miles from Overton to Chawton, where Austen lived her last eight years. I get off my second bus near Alton’s Assembly Rooms to see a newly unveiled bust of the author.

Today’s plan is a patchwork of four shorter walks, starting with the 2.5km/1½-mile historical trail that links the market town of Alton with Chawton. The route along pavements would suit ramblers with buggies or wheelchairs. There are still buildings Austen knew on Alton’s High Street – her doctor’s house, her brother’s bank and The Swan, where the coach to London stopped – but she might be surprised to find the subway under the A31 painted with her quotes and silhouettes.

Beyond it, like stepping through a time portal, is thatched and leafy Chawton. The whole village is sweet with honey-scented lime blossom and bees are humming round the hollyhocks. I drop into Jane Austen’s old house to gawp at her tiny writing table and hand-stitched patchwork, and sit on a deckchair in the flowering garden (pre-booking essential; £14/£6.25 for adults/children, janeaustens.house).

Discovering Austen’s Chawton and Winchester

Approaching Chawton House, at the far end of the village, a linden avenue leads visitors past open parkland. In Emma, Austen describes the ‘delicious shade of a broad short avenue of limes’ leading to ‘a sweet view – sweet to the eye and the mind’.

On the edge of the churchyard, where her mother and sister are buried, a bronze statue captures the writer mid-stride, looking out across the fields. ‘The one thing we know she did in this village is walk,’ says Katie Childs, chief executive of Chawton House, over a coffee in the Old Kitchen Tearoom.

A legacy from distant childless relatives, Chawton House was home to Austen’s brother Edward and she knew this grand manor intimately, calling it the ‘Great House’. Swallows nest in the porch and swoop overhead. In the walled garden, heavy-headed roses climb through the orchard, snowing fragrant petals onto sandy paths. Above borders of sweet Williams and marigolds, the mossy fruit trees are already bending under their harvest: medlars, plums, espaliered pears and enough apples to use in the café’s cake throughout the winter. There’s a wooded area, too (a ‘wilderness’) and a shrubbery – both very Austenian features.

The walk from Chawton to nearby Farringdon was a favourite with Austen and there’s a pleasant 7km/4½-mile circular route, returning along the disused Watercress Line railway. But today I opt for a stroll around Chawton House’s 275-acre park, open for walkers and partly accessible. With its waymarked trails, library of books by women, extensive gardens, summer theatre programme and excellent tearoom, there are lots of reasons to visit Chawton (tickets from £8/£6 for adults/children, chawtonhouse.org).

I catch the bus back via Winchester and pay my respects to Austen’s grave in the cathedral. A new trail around the city takes in Georgian buildings, the River Itchen, the house where the writer spent her final weeks and the P&G Wells bookshop (still open!) where her family bought their books. You can see her purses in the City Museum and a poem she wrote to Anne Lefroy in the cathedral’s exhibition (until 19 October, £13/£5, winchester-cathedral.org.uk).

An Austenian happy ending

After supper, I amble round the 4km/ 2½-mile circuit of quiet, leafy lanes billed as Overton in Jane Austen’s time, passing mills and rose-wreathed cottages. The accompanying leaflet unearths numerous local links, but I’m happy just to stroll through the dappled evening, listening to cooing doves and sighing willows. The fast-flowing river, with fish dimpling the surface and swans nesting on the banks, reflects the sparks of fading light as it has for centuries while the setting sun glows gold behind the trees.

Walk it: explore the landscapes that inspired Austen

Distance: The main Overton Trails are 4km/2½ miles round the village and 14.5km/9 miles out to Steventon and back (overtonparishcouncil.gov.uk/ overton-jane-austen-trails). The many routes around Chawton include the 7km/4½-mile walk to Farringdon (visit-hampshire.co.uk/things-to-do/ jane-austen-circular-walk-p60383) and the 2.5km/1½-mile trail to Alton (visit-hampshire.co.uk/things-todo/ jane-austen-trail-walk-altonto- chawton-p360641). There’s also a new 3km/2-mile trail around Winchester (visitwinchester.co.uk/ business-directory/jane-austenswinchester-trail).

Maps and guides: OS Explorer 144 and OS Landranger 185 and 186, plus the walk guides listed above.

Accommodation: The White Hart, Overton (B&B doubles from about £90, whitehartoverton.co.uk). Budget options include Winchester Travelodge (from £40, travelodge.co.uk/hotels/660/winchester-hotel). TRANSPORT Buses 76 from Basingstoke and 86 from Winchester (both Stagecoach) stop regularly in Overton at the start of both walking trails. There are also connections from Basingstoke and Winchester to Alton and Chawton. A Gold DayRider ticket gives a full day’s local bus travel for £8.50 (stagecoachbus.com). Trains to Overton station from London Waterloo stop about 800m/½ mile from the route (southwesternrailway.com).

More information: visit-hampshire.co.uk.

Walk & Talk: Michael Rosen

His bestseller We’re Going on a Bear Hunt has been inspiring family rambles for two generations. But when Covid left author and broadcaster Michael Rosen in a coma, he had to learn to walk again, one agonising step at a time.

St James' Way: The English Camino

There’s no need to go overseas to walk a camino, one of the medieval pilgrim routes heading towards Santiago de Compostela in Spain. The recently waymarked St James’ Way wends its way through southern England